|

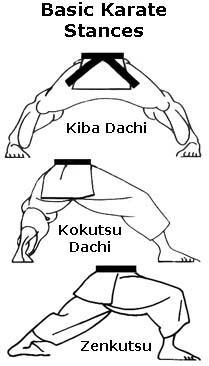

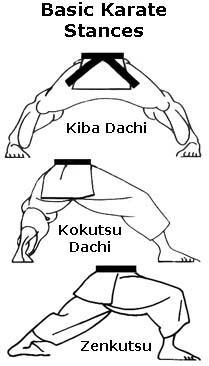

Goju-ryu posture very similar to the

opening posture in one of the first two

Pinan kata. In the Shotokan Heian

version, the stance is much longer

and much less mobile. |

I came across an interesting post the other day on an Internet forum. It was by a guy who was a bit disillusioned but still searching for meaning in his kata--kata that he had been practicing for more than twenty years, I think. He was asking all the right questions, it seems to me: what message was contained in the repetition of techniques in kata? Are there patterns or sequences of techniques, and if so what do they signify? Are there themes that certain kata focus on? The problem was that he practiced Shotokan karate--a style, it seems to me, that is so far removed from its Okinawan origins as to make it nearly impossible to determine the original intent (or original

bunkai) of any of the movements that make up the kata.

|

The stances of Shotokan

are generally wider and longer

than their Shorin antecedents. |

After doing a little foraging on the Internet, I found that this searching into the meaning of Shotokan kata is not really new at all. Apparently certain Shotokan practitioners have been bucking the system for years--I'm only hinting at the chilling effects powerful international organizations may have on individual initiative and any questioning of the official line--practitioners like Bryce Fleming, Elmar Schmeisser, Bill Burgar, and John Vengel. Fleming even cites some of my own thoughts on kata analysis in a nicely written article titled

"Bunkai: Returning Kata to the core of Karate," though I'm not sure he understood what I was trying to say in every case, which may very well be my own fault, as I'm not sure any of my ideas are applicable to any other art than Goju-ryu. But it is interesting to me that there is an attempt to place kata and the study of kata applications back in the forefront of popular karate study, and Shotokan may very well be the most popular karate style in the world. The problem is, how do you reconstruct the original intent (

bunkai) of a kata after the kata has been changed? It's like trying to figure out what Shakespeare was saying in

Macbeth after only watching the episode of

The Simpsons that referenced it, or as someone once put it, reconstructing the original hits when all you have are the Weird Al Yankovic versions. Well, maybe not quite that bad, but still.

Of course, not all of the movements have been altered, but if one movement in a sequence is altered enough, it will alter how one may interpret the rest of the sequence. Correct me if I'm wrong, since I'm certainly no authority on Shorin-ryu, but if you change a

neko-ashi-dachi (cat stance) to a

kokutsu dachi (back stance), as Shotokan does with its Heian versions of the Pinan series, it seems to me that you will be hard pressed to

"see" the kick (whether a kick with the knee or the foot) in the sequence. And once you change the cat stance to a back stance, the upper body and arms are also re-oriented in relation to the possible attacker, so they may further alter how one interprets the techniques. One could certainly argue, as many do, that there's no guarantee that even any school of Okinawan karate--Goju, Uechi, or Shorin--has preserved the original way that any particular kata was performed; they've all undergone change (though that's just an assumption in itself and with no more certitude really than to argue that nothing has changed). But that still doesn't mean that all changes are equal--that the

bunkai you find in Shotokan is as valid as the

bunkai you find in Shorin kata.

All of this, of course, begs the question: Are all versions of kata equally valid? Is the Shotokan version of a kata (and by implication the

bunkai) as valid as the Shorin version of the same kata? Is the Isshinryu version of a kata as valid as the Goju version of the same kata? What about more minor differences we find in Meibukan or Shodokan or Jundokan or Shoreikan versions of the same kata? Is it all equally valid because you can, with varying degrees of effort and imaginative interpretation, manage to make a

bunkai that fits the kata movements? It won't be the same

bunkai necessarily, but so what?! You got a problem with that?

Well, yes. I actually think these are troubling questions, though I know they don't seem to bother the vast majority of karate practitioners out there. Explaining kata movement, or at least the debate over it, is as popular among Shotokan practitioners as it is among the practitioners of the various Okinawan styles apparently, at least after you tire of the tournaments and such. And it would seem that the majority of people who practice karate are pretty satisfied with what they're getting. Otherwise, I can only hope, there would be more people out there pointing fingers and declaring that "the emperor has no clothes," because it's fairly obvious that a lot of the

bunkai out there is crap. The problem is that even though you may have a

bunkai to explain a technique that has been altered--as the example of the change in

neko-ashi-dachi above--in altering the kata, you have not only altered the

bunkai, but you more than likely have altered the

themes the kata is exploring and probably the

principles of the system as well.

And it can get even more problematic than that. Fleming, citing Harry Cook, writes that "Gusukuma, an original student of Ankoh Itosu," (one of the early Shorin masters) said that "Itosu didn't know all the applications and felt that some of the movements [of kata] were just for show" (Fleming). If Itosu didn't know the applications for all of the moves in the classical kata of Shorin-ryu, how did he go about creating the Pinan series of kata? If you don't know what all of the applications are then how do you know which techniques to use in the Pinan series and which to leave out? Are you taking isolated techniques out, techniques that are actually part of sequences? What themes and principles are you going to use as the basis of these new kata if you're not sure of the applications in the first place? If the

embusen (pattern) of the original kata don't carry any message that might demonstrate

tai sabaki (off-line movement) because the applications are not fully understood, for instance, what message, if

any, will students be able to extract from the "H" or "I" pattern of the Pinan kata? And when you don't understand something, the very human tendency to change it to something you do understand--or

create something you do understand--often steps in and takes over. Not to throw all of Shorin-ryu out with the bath water, but the Pinan series forms a large part of the curriculum in Shorin as well as Shotokan schools, so if you are learning to decipher kata through an analysis of the Pinan kata, you see the problem.

I read stuff over and over again from Shotokan practitioners who say that kata has no purpose other than as a performance art, that it's pointless to even look for meaning in kata. And no wonder, given its history. Certainly it's worth trying to find meaning in kata, but if you're practicing an art that is so far removed from its origins, it's going to be a hard slog at best. If you ask me, which of course you didn't, and me being from New England, I'd have to say, "Ya can't get they-ahh from hee-yahhh."