Perhaps he didn't mean to imply anything in the least disparaging. His book, A Walk in the Woods, is wonderfully entertaining, though it seems to find much of its humor in the ineptitude of its protagonists, in the unlikeliness of their shared adventure to hike the Appalachian Trail. Yet I wonder why we should feel so out of place in these primal surroundings, which of course aren't even so primal anymore, now that we've fenced it in and preserved it as a state park or labeled it a conservation area.

The other thing about that quote is that it makes it sound as though it's all the same, that it's all just a bunch of trees, one pretty much like the next. Sometimes I think this tendency to generalize, to smooth out all the rough edges and do away with differences, is quite human. I remember it was almost a common retort when we were children to respond to a friend who might correct something you said with the quick rejoinder, "Same difference." I'm sure that ended it when I was a child, though I'm not at all sure what it really means. But it got me thinking about the ways we tend to treat techniques in kata when they appear to be the same--that is, we assume that techniques that look the same must function the same in kata.

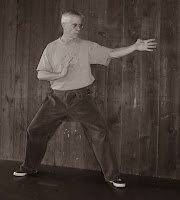

|

| Open hand block from Shisochin. |

|

| Open hand "block" from Seipai. |

It is this bent of mind that tends to divorce kata techniques from their applications or bunkai. The open-hand techniques after the first turn in Seisan kata--turning to the south after the opening sequence of techniques in the front-facing line--are another example of this, I think. After the initial right arm circular block and the left palm strike, the kata moves into a right-foot-forward basic stance while the left arm and left palm is brought down and the right arm and palm is brought up, finishing with the right palm rotated and facing forward. This same technique is done once more, stepping forward into a left-foot-forward basic stance, before pivoting to the right to finish the sequence with the "punches" and kick to the west. In some schools, these techniques are done twice--first stepping with the right and again stepping with the left--and in others, four times, twice with each hand and foot. In either case, the "message" of the kata is that the two techniques are meant to function together; that is, both are part of the controlling technique of the bunkai sequence, following the initial block and attack of the first technique that occurs on the turn. (The repetition of four of these techniques suggests that both sides are being shown or practiced within the kata. Either that or an attempt to bring the kata back to the original starting point at the end, though this certainly does not generally seem to be of any importance in Okinawan kata.)

|

| The second palm-up technique from Seisan kata just before the pivot to the west. |

This, of course, raises a difficult issue. Kata should always inform bunkai. Otherwise we're left with all manner of creative interpretations that don't bear the least resemblance to kata movement. But kata was meant to preserve bunkai or self-defense applications. We have, I think, an innate desire to generalize movement, to homogenize it in order to understand it. But from a certain perspective, there really is no such thing as standard or basic technique, no generic chest blocks, for example, when it comes to the classical kata if each scenario is unique. Certainly there is good technique and bad technique, but the performance of any given technique is really dependent on how it is used in a sequence of kata movements. Occasionally, I think, over time, some of these movements, for whatever reason, have undergone subtle changes--differences have been dropped, rough edges have been smoothed out, until what was once only similar is now seen as the same technique.

When I was a lot younger, I used to look at every tree, judging whether it was a good climbing tree or not. I know a lumberman who would look at trees and size up the quality of the wood--was it soft or hard, straight-grained or not. The techniques of kata are the same--they're not generic, but rather dependent on how they fit into kata, how they are used within the self-defense scenarios of Goju-ryu kata. Like trees, I suspect, they're all different.

[For a more detailed discussion of these techniques see my book, The Kata and Bunkai of Goju-Ryu,

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/562446/the-kata-and-bunkai-of-goju-ryu-karate-by-giles-hopkins/9781623171995/]