I was thinking about this the other day...our tendency to homogenize things that are similar, how over time we smooth out the edges and look for commonalities until we've erased the differences altogether. That may be overstating the case, but it got me to thinking.

I was thinking about this the other day...our tendency to homogenize things that are similar, how over time we smooth out the edges and look for commonalities until we've erased the differences altogether. That may be overstating the case, but it got me to thinking.I was out for a walk in the woods, engaging in a bit of "woods bathing," one of my favorite activities, when I found myself thinking about the time my father "borrowed" my rock collection. I think I must have been seven or eight years old. My father was helping out the Boy Scouts with their Klondike Derby. My older brother was in the scout troop--he would go on to become an eagle scout and I would become a scout dropout, never really comfortable with dressing up as a para-military youth gang, though the questionable leadership of our assistant scout master was probably more to blame, either that or the '60s. Anyway, the Klondike Derby was a sort of winter carnival with the scouts dragging sleds through the snow, completing tasks, and accumulating "gold nuggets." Of course, someone needed to supply the "gold nuggets," and that was the job my father took on. He "borrowed" the big Lincoln Log barrel I had filled up with my special rock collection, spread them all out on his work bench, and spray painted them all gold. When I found out, I was distraught. My father didn't understand at the time. He offered to get me more rocks, but this was a collection of "special" rocks that I had been collecting for quite some time. They were just rocks I had found on the road or in the woods, but they were all special to a little kid. And they were all different...at least until they all got a thick coat of gold paint.

I wasn't consciously thinking about childhood events or kicking up "special" stones hidden under the fall leaves. I was just sort of wondering about that unique quality that all things have, especially things that seem similar. You really notice it in the fall, when the trails are covered with leaves. Late in the season, when all the leaves have turned brown, they all seem to be the same unless you look closely. Then, you can't find any two that are really exactly the same. The trails up around Fitzgerald Lake are mostly covered with oak leaves, but still they're all different.

|

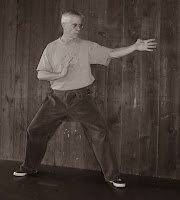

| Beginning movement of the mawashi uke. |

I'm not at all sure how insidious or widespread this tendency to homogenize may be or how it may have affected kata over the years or generations. Certainly when we name techniques in kata, there is the danger that we may be homogenizing movements that are actually quite different, especially if the names we give the movements are meant solely to describe the look of the movement rather than how it is used.

|

| Beginning movement of the other one. |

The second mawashi-like technique occurs at the end of Saifa, at the end of Seipai, at the end of Seisan, in the middle of Kururunfa and again at the end, and it is shown three times in Suparinpei (interestingly both kinds occur in Suparinpei). Each of these mawashi-like techniques is done in cat stance or neko ashi dachi. The difference is in how they function. This second mawashi-like technique is a finishing technique, meant to twist the head or break the neck of the opponent. These techniques are tacked onto the end of longer bunkai sequences in the classical kata. They function differently from the other mawashi and consequently should be done differently in kata. More specifically, when the mawashi is associated with the cat stance (which itself implies a knee kick), the left hand does not pass under the right elbow or forearm, or, on the other side, the right hand does not pass under the left elbow or forearm. When the mawashi is associated with basic stance or sanchin dachi, the right hand does pass under the left elbow or forearm, or, on the other side, the left hand passes under the right elbow or forearm. What gets confusing, I suppose, is that the end position--both palms facing forward with one hand pointing up and the other pointing down--looks the same, except for the stance.

The second mawashi-like technique occurs at the end of Saifa, at the end of Seipai, at the end of Seisan, in the middle of Kururunfa and again at the end, and it is shown three times in Suparinpei (interestingly both kinds occur in Suparinpei). Each of these mawashi-like techniques is done in cat stance or neko ashi dachi. The difference is in how they function. This second mawashi-like technique is a finishing technique, meant to twist the head or break the neck of the opponent. These techniques are tacked onto the end of longer bunkai sequences in the classical kata. They function differently from the other mawashi and consequently should be done differently in kata. More specifically, when the mawashi is associated with the cat stance (which itself implies a knee kick), the left hand does not pass under the right elbow or forearm, or, on the other side, the right hand does not pass under the left elbow or forearm. When the mawashi is associated with basic stance or sanchin dachi, the right hand does pass under the left elbow or forearm, or, on the other side, the left hand passes under the right elbow or forearm. What gets confusing, I suppose, is that the end position--both palms facing forward with one hand pointing up and the other pointing down--looks the same, except for the stance. These are the two kinds of mawashi techniques we see in the classical kata of Goju-ryu, and, on second thought, they probably have nothing to do with rocks and trees and walking in the woods. But when the paths diverge, I can't help thinking of that line from Robert Frost. How does it go?

These are the two kinds of mawashi techniques we see in the classical kata of Goju-ryu, and, on second thought, they probably have nothing to do with rocks and trees and walking in the woods. But when the paths diverge, I can't help thinking of that line from Robert Frost. How does it go?