Snow showers. I'm not even sure what that means, but they left a light, powdery coating of snow on everything. A dusting, they call it. The trail cuts a white, meandering path through the woods, and even the rocks along the path catch the snow in places, like white shadows clinging to small indentations, protected for the moment from the winter sun or gusts of wind. It almost looks as though no one has passed this way, no footprints to mark the trail and scuff up bits of leaves and gravel. I might be the only one who has passed this way, at least today, because, of course, it's a trail. Someone made it, carved it out of the forest, cut saplings and cleared brush.

Snow showers. I'm not even sure what that means, but they left a light, powdery coating of snow on everything. A dusting, they call it. The trail cuts a white, meandering path through the woods, and even the rocks along the path catch the snow in places, like white shadows clinging to small indentations, protected for the moment from the winter sun or gusts of wind. It almost looks as though no one has passed this way, no footprints to mark the trail and scuff up bits of leaves and gravel. I might be the only one who has passed this way, at least today, because, of course, it's a trail. Someone made it, carved it out of the forest, cut saplings and cleared brush.I'm thinking metaphorically again, walking along the trail, mentally practicing kata, thinking about bunkai and imagining the other side, the side that's so hard to picture; the attacking side. This sort of metaphorical thinking reminds me of that book by Murakami, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. Or that line from Il Postino where Mario asks Neruda, "You mean then that...the whole world is the metaphor for something else?" And with a abashed look, Mario says, "I'm talking crap." And Neruda says, "No, not at all."

Someone made kata, these patterns of movement that we use to remember techniques of self defense, that we use to learn the martial principles of movement. But the patterns are confusing and seemingly as haphazardly composed as a meandering trail heading off into the woods. No two trails exactly the same. No two kata alike in structure, conforming to the same rules one might use to decipher their patterns. And yet someone passed this way before, left marks, however faint, that would point the way, like trail markers, and explain how we might go about figuring out these seemingly arcane and esoteric movements.

Are they arcane and esoteric? Certainly they are, to us, a bit anachronistic, in a way, a part of a cultural milieu and time period when one might have needed to defend one's life, fighting to the death with lethal techniques, as anachronistic as many of the techniques that seem to depend on one grabbing the topknot or queue of one's attacker. But esoteric? The effectiveness of most techniques, arguably, is based largely on their simplicity, not their complexity or the difficulty one might have in learning them. The difficulty lies mainly in trying to explain movements and techniques that we can only half see. With kata, we only see the defender's response to an attack. We can only imagine the other side, and this often influences how we interpret the techniques of kata.

And whoever created these kata, certainly did not make it easy. If a single person put the techniques of these kata together--I'm thinking of the classical subjects of Goju-ryu from Saifa to Suparinpei--then I would expect the patterns to be as uniform and predictable as the set of Pinan kata or the Gekisai kata of the 20th century. But they're not. Seipai kata, for example, is largely asymmetrical--with at least the first three sequences not showing any repetition--using the left hand to "block" and the right hand for the initial attack (which is also true of the fourth sequence, though that sequence is repeated on the other side). Each of the first four sequences--there are seemingly five total sequences, though the fifth sequence shows a variation, in part, on the other side--is shown in its entirety; that is, with an initial receiving, a controlling or bridging technique, and a finishing technique. This is not the same pattern we see in Seiunchin, for example, which, aside from its set of three opening techniques in shiko dachi, repeats most of its techniques on both the right and left sides--that is, in response to a right or left attack--whereas Seipai only repeats the fourth sequence. But even in Seiunchin we have a pattern that is "interrupted," where some of the sequences, unlike most of the sequences of Seipai, only show the final techniques tacked onto the second or final repetition. This is true of the opening sequence of moves, the high-low techniques in shiko dachi, and the "elbow" techniques--that is, the first sequence, the third sequence, and the final sequence.

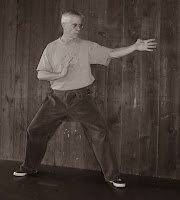

|

| Core receiving technique from Sanseiru when used with the stepping turn. |

Sanseiru kata, on the other hand, shows significant repetition in its middle section, repeating this "core" movement--chest "block," kick, "elbow," "punch," kick series--three times, and using an opening sequence that is merely a variation of similar techniques. And Seisan is entirely different again, showing three variations of what is essentially the same bunkai in the three sequences that follow the opening series of repetitive basic techniques--the three punches, three circular blocks, and three palm-up/palm-down techniques with knee kicks followed by a grab and kick.

There are so many structural variations, in fact, in just these four kata that it certainly seems to suggest different origins or sources, and it certainly adds to the difficulty one has in trying to understand the original bunkai of the different kata. And yet, different kata structures do not change

|

| The bridging technique of the final sequence in Sanseiru. |

This may seem heretical or at the very least blasphemous, but it's merely another way of seeing the sequences of a kata, another way of practicing kata bunkai. For example: If we take the first sequence of Seiunchin kata described above, we see that the first two opening shiko dachi techniques are incomplete, with the finishing technique only attached to the third repetition--this is the push forward with the "supported punch" and elbow attack. If we attach the finishing technique to the first of these steps into shiko dachi (same as the third) and/or the second of these (on the opposite side), we are not really altering the intent of the kata. We're merely illustrating it in another way, completing the sequences that are only shown in part. We could do the same thing with the core double arm receiving techniques of Sanseiru, attaching them to the open hand bridging techniques we find towards the end of the kata.

Certainly what we find is that the flow of kata that we have become accustomed to is interrupted, but the real intent of kata is to act as a repository for self-defense techniques, not to be practiced as a performance piece. In fact, the less we see kata as a performance piece for winning trophies at tournaments, the more we may begin to understand its patterns, its structure, and thereby its bunkai.

[For a more detailed discussion of these techniques see my book, The Kata and Bunkai of Goju-Ryu, here.]